Why this article exists (before we look at any charts)

In the System Baseline edition of The Reliability Illusion, we established a simple but critical shift:

Vessel schedule reliability doesn’t break at arrival.

It breaks inside the cargo receiving window.

That window - defined by the Earliest Return Date (ERD) and the CY Cutoff - is where export execution actually happens.

This edition applies the same framework to Yang Ming (YMLU) to understand how cargo receiving windows behave in practice - where they stay predictable, and where they don’t.

All terms used here are defined in the Reliability Series - Methodology Appendix:

https://www.tradelanes.co/blog/reliability-series-methodology-appendix

Data scope (Yang Ming sample)

This analysis is based on an observational system sample of executable export port-calls and is not a statistically randomized sample.

- Port-calls: 118

- Vessels: 45

- Ports: 7

- Carrier: YMLU (Yang Ming)

Filters applied:

- ERD and CY Cutoff both required

- Drift >40 days treated as data error and excluded

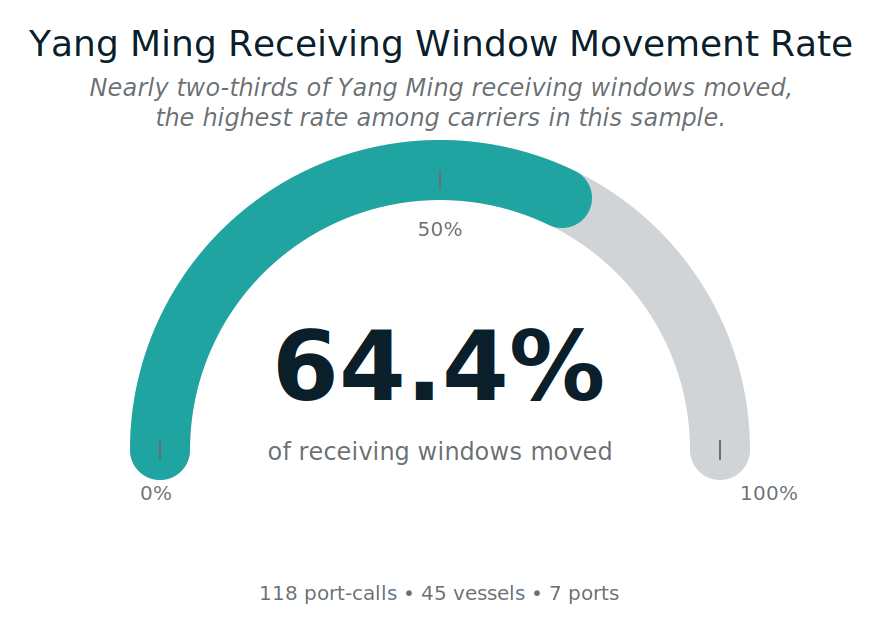

Section 1 - How often do Yang Ming receiving windows actually move?

A receiving window is considered moved if either ERD or CY Cutoff shifts by one calendar day or more from its originally published value.

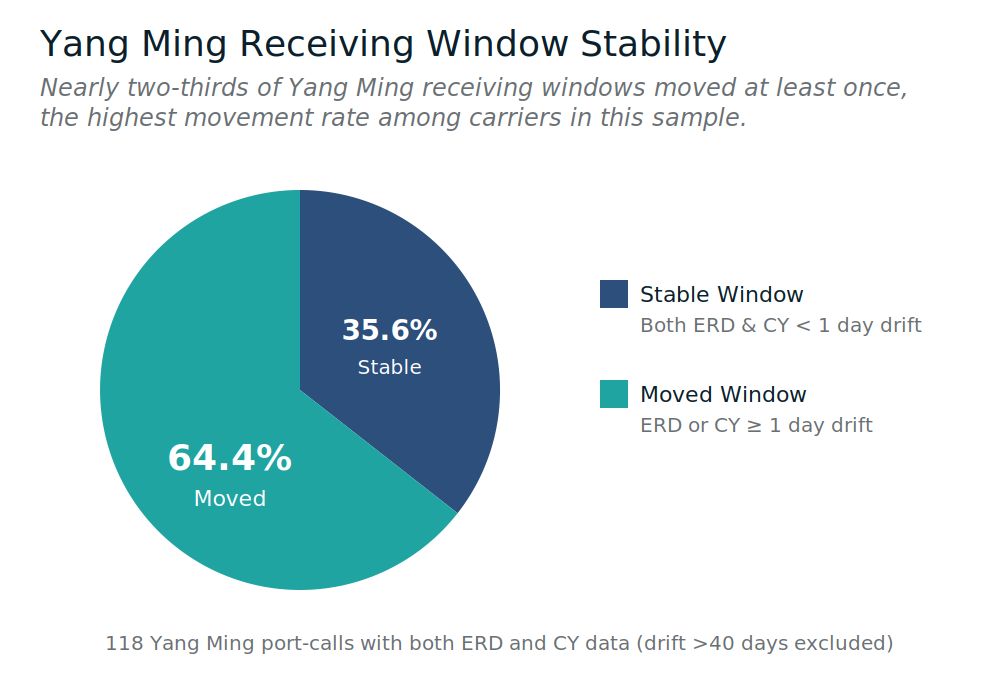

Figure 1 - Receiving Window Stability (Yang Ming)

- Stable receiving windows: 35.59%

- Moved receiving windows: 64.41%

Plain English meaning:

For Yang Ming in this sample, receiving window movement is the majority state. That doesn’t automatically mean something is “wrong” - but it does mean exporters should expect plans to require re-validation more often than not.

Section 2 - Drift isn’t chaos; it has a shape

Drift measures how far ERDs or CY Cutoffs move between original and final values, expressed in calendar days.

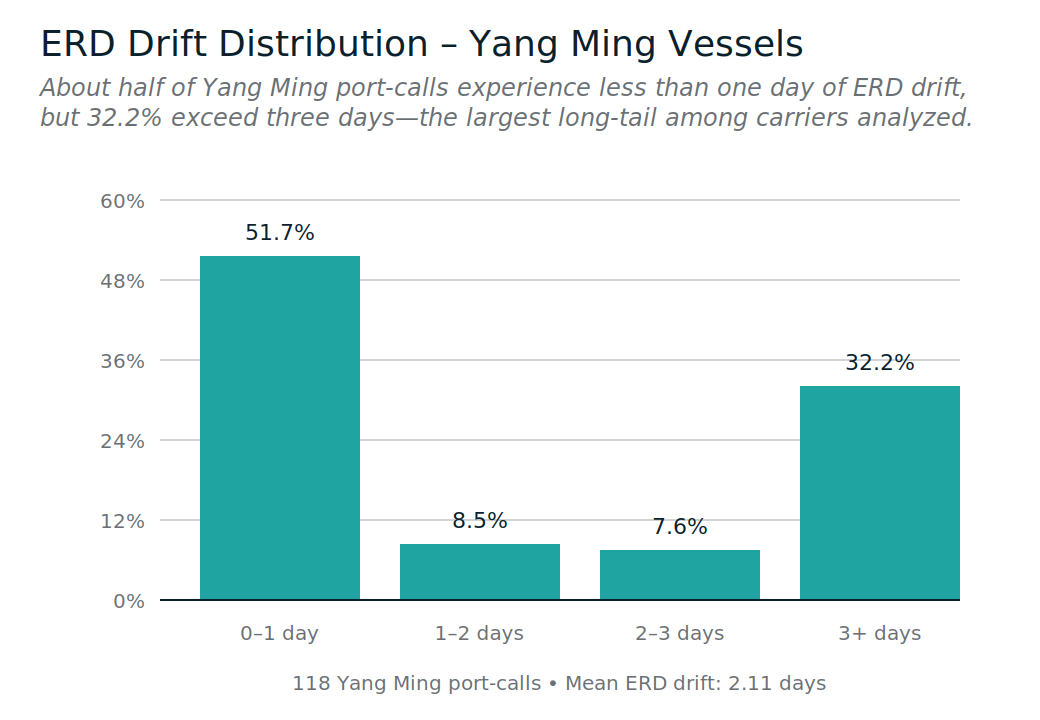

Figure 2 - ERD Drift Distribution (Yang Ming)

- 0-1 day: 51.69%

- 1-2 days: 8.47%

- 2-3 days: 7.63%

- 3+ days: 32.20%

Plain English meaning:

Yang Ming shows a meaningful tail: nearly one in three port-calls experienced 3+ days of ERD drift. That tail is where execution pain concentrates.

Static buffers are built for the middle of the curve.

Operational pain lives in the tail.

Section 3 - ERD vs CY: where Yang Ming risk concentrates

Across this sample, ERD drift is higher on average than CY drift, even though CY still exceeds ERD at the 1-day threshold.

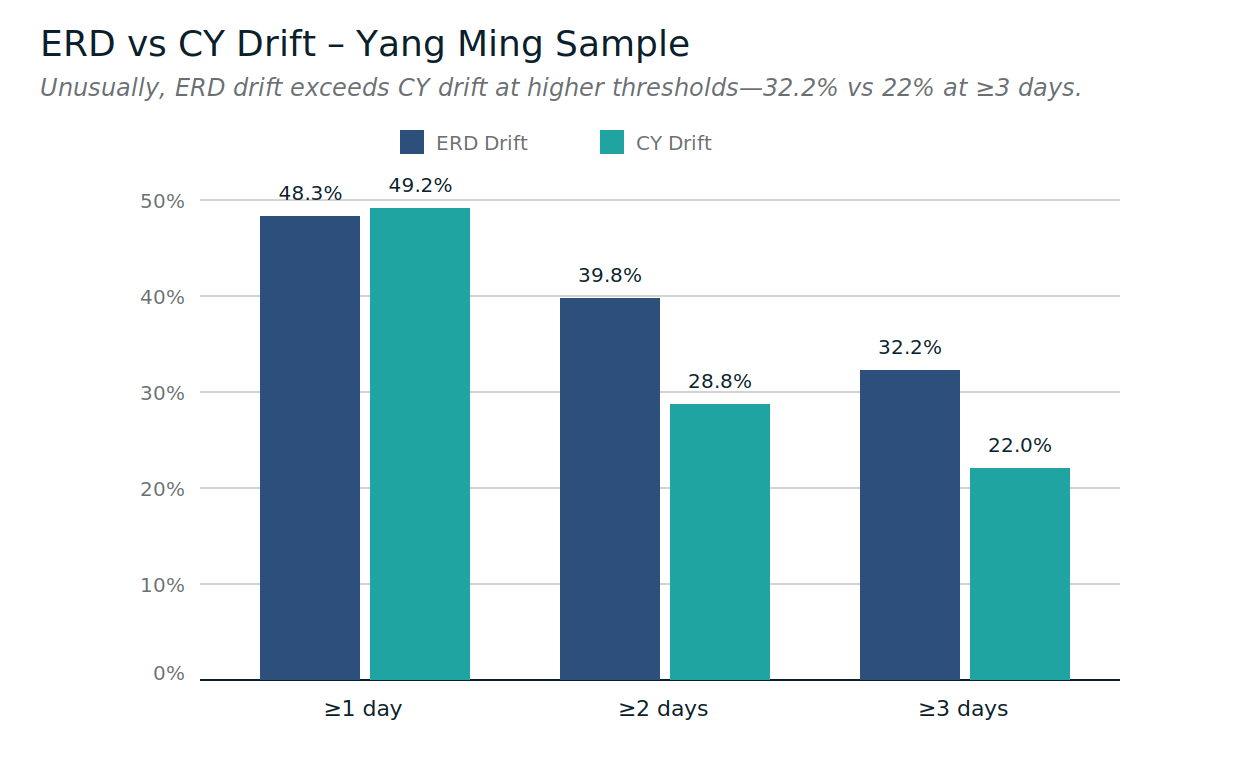

Figure 3 - ERD vs CY Drift (Yang Ming)

Average drift:

- Mean ERD drift: 2.11 days

- Mean CY drift: 1.76 days

Threshold comparison:

- ≥1 day drift: ERD 48.31% vs CY 49.15%

- ≥2 days drift: ERD 39.83% vs CY 28.81%

- ≥3 days drift: ERD 32.20% vs CY 22.03%

Plain English meaning:

This is a useful reminder that “the constraint” can differ by carrier. In this sample, ERD movement becomes the dominant driver as drift grows (2+ and 3+ days), while CY remains the more common issue at the 1-day threshold.

Operationally, that often feels like:

- early acceptance dates shifting enough to force replans, and

- cutoffs still moving often enough to create late friction.

Section 4 - Timing matters more than averages

A late-stage change is defined as a change to ERD or CY Cutoff that occurs within the final 72 hours before the receiving window opens.

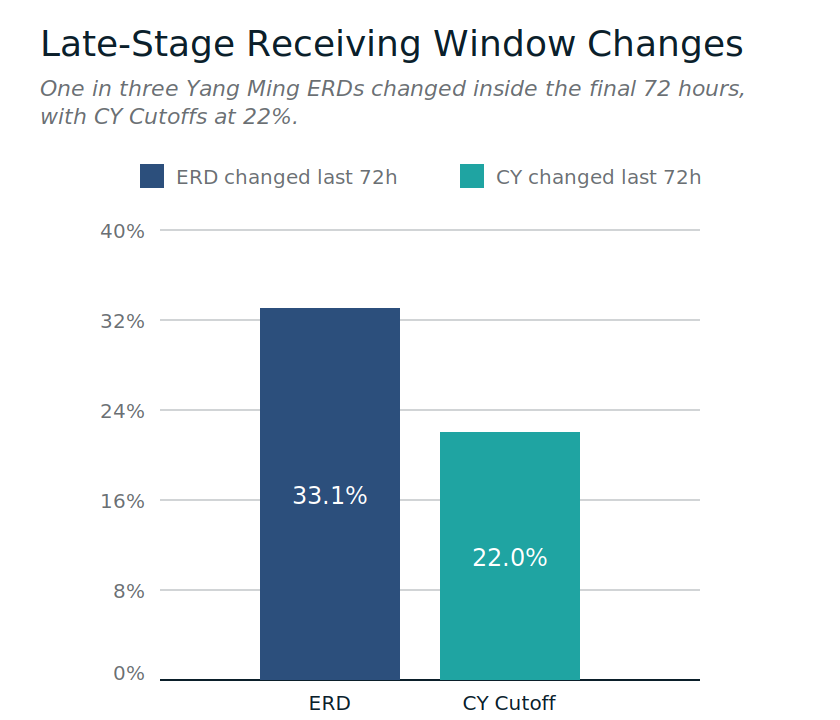

Figure 4 - Late-Stage Receiving Window Changes (Yang Ming)

- ERD changed in last 72 hours: 33.05%

- CY Cutoff changed in last 72 hours: 22.03%

Plain English meaning:

Roughly one in three ERDs and about one in five CY Cutoffs changed inside the final 72 hours. That is the execution lock-in problem: the plan can look workable until close-in changes reduce options.

So far, we’ve looked at how windows move.

Next, we look at where.

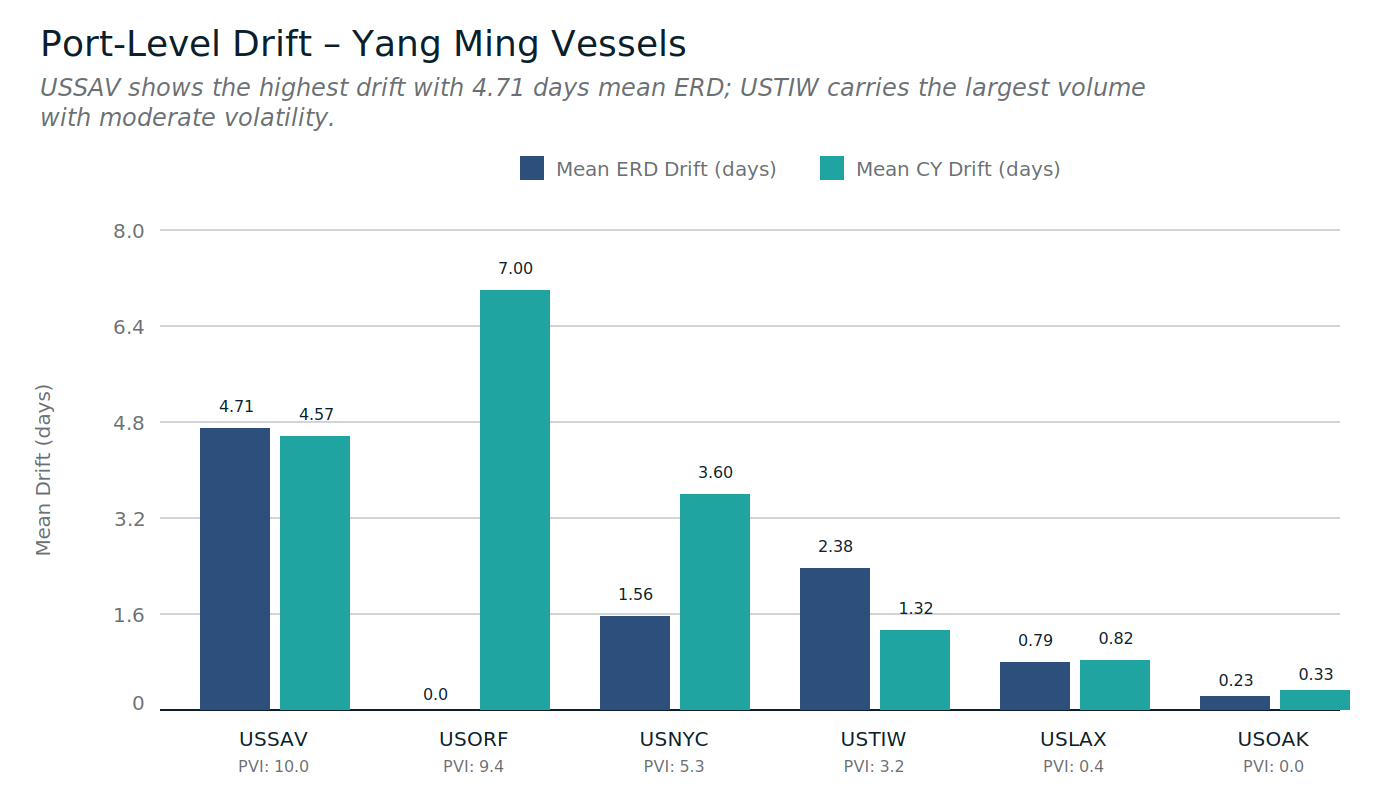

Section 5 - Volatility is not evenly distributed across ports (Yang Ming)

The Port Volatility Index (PVI) reflects how quickly static planning assumptions break at a port.

Figure 5 - Port-Level Drift (Yang Ming)

Below are Yang Ming’s port environments in this sample, ordered by PVI. Ports with very small sample sizes should be interpreted cautiously.

USSAV (PVI 10.0, n=14)

- Mean ERD drift: 4.71 days

- Mean CY drift: 4.57 days

- Stable window rate: 7.14%

- ERD late-stage change: 35.71%

- CY late-stage change: 28.57%

What this feels like:

This is where volatility concentrates for Yang Ming in this dataset. Both ERD and CY move far enough that static buffers stop being reliable. Execution becomes a re-validation workflow.

USNYC (PVI 5.3, n=9)

- Mean ERD drift: 1.56 days

- Mean CY drift: 3.60 days

- Stable window rate: 33.33%

- ERD late-stage change: 33.33%

- CY late-stage change: 22.22%

What this feels like:

A “CY-dominant” port environment. ERDs move, but CY moves more and can break plans late.

USTIW (PVI 3.2, n=62)

- Mean ERD drift: 2.38 days

- Mean CY drift: 1.32 days

- Stable window rate: 30.65%

- ERD late-stage change: 41.94%

- CY late-stage change: 14.52%

What this feels like:

ERD volatility dominates here, and late-stage ERD change is high. Exporters can be forced into replans earlier than expected.

USLAX (PVI 0.4, n=25)

- Mean ERD drift: 0.79 days

- Mean CY drift: 0.82 days

- Stable window rate: 56.00%

- ERD late-stage change: 12.00%

- CY late-stage change: 28.00%

What this feels like:

More predictable overall, with CY timing still worth watching closer to execution.

USOAK (PVI 0.0, n=6)

- Mean ERD drift: 0.23 days

- Mean CY drift: 0.33 days

- Stable window rate: 66.67%

- ERD late-stage change: 33.33%

- CY late-stage change: 33.33%

What this feels like:

Small sample, but a common pattern: low average drift does not guarantee low late-stage risk.

USORF (PVI 9.4, n=1) and USCHS (PVI 0.3, n=1)

These ports have one port-call each in this sample. They should not be over-interpreted.

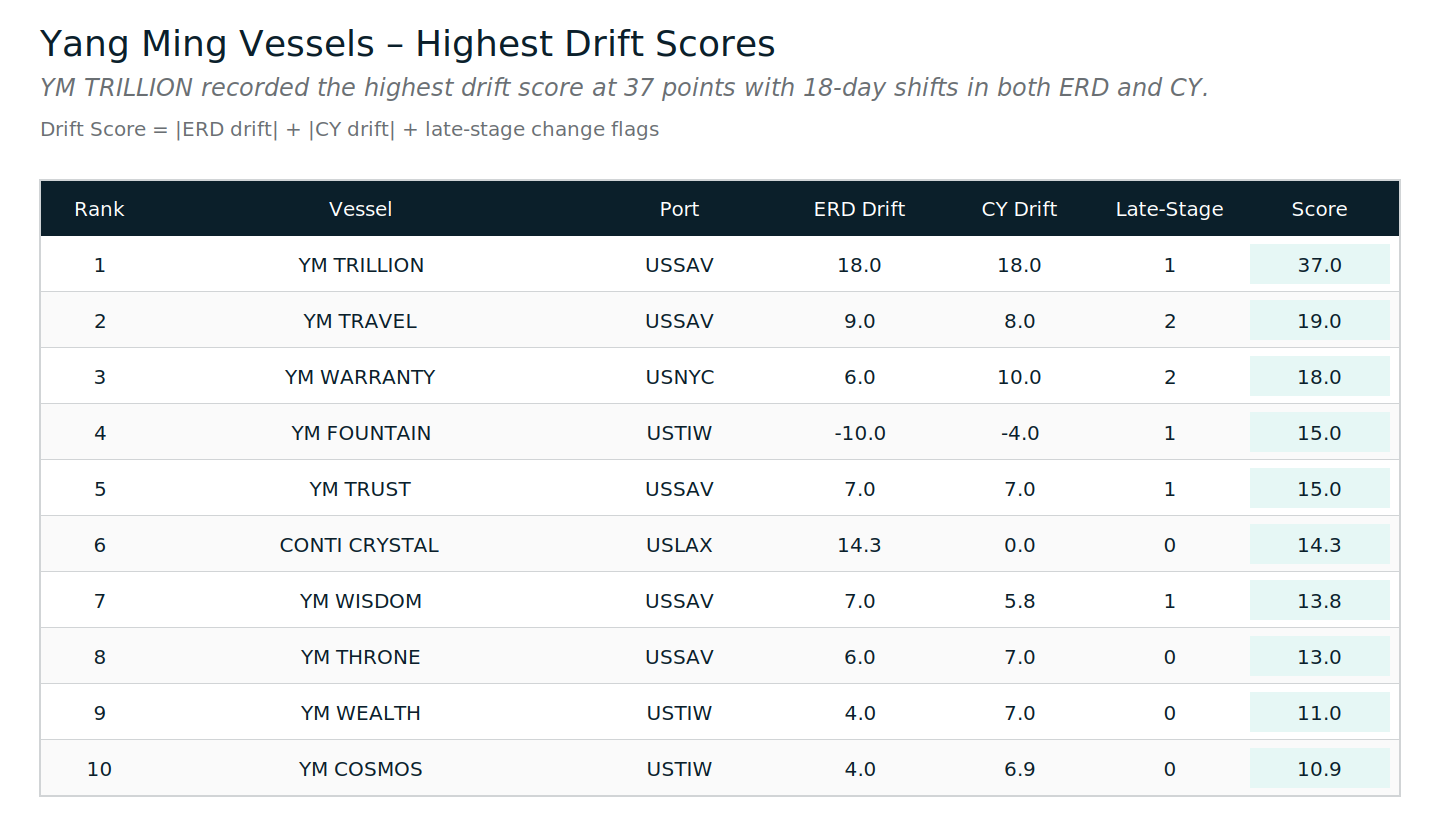

Section 6 - Severity still exists, even when averages look manageable

Figure 6 - Top 10 Highest-Severity Yang Ming Events

Top examples:

- YM TRILLION (USSAV): ERD 18d, CY 18d, late-stage 1, drift score 37

- YM TRAVEL (USSAV): ERD 9d, CY 8d, late-stage 2, drift score 19

- YM WARRANTY (USNYC): ERD 6d, CY 10d, late-stage 2, drift score 18

Plain English meaning:

These are stress tests, not typical shipments. They show how quickly drift can stack when multiple changes coincide, especially in the highest-volatility port environments.

Static buffers fail in these scenarios by design.

Section 7 - The KPI that matters for Yang Ming

Figure 7 - Receiving Window Movement Rate (Yang Ming)

- Moved receiving windows: 64.41%

- Stable receiving windows: 35.59%

- Scope: 118 port-calls • 45 vessels • 7 ports

Plain English meaning:

For Yang Ming in this sample, movement is the norm. The operational risk is driven by both magnitude (the 3+ day tail) and timing (late-stage changes).

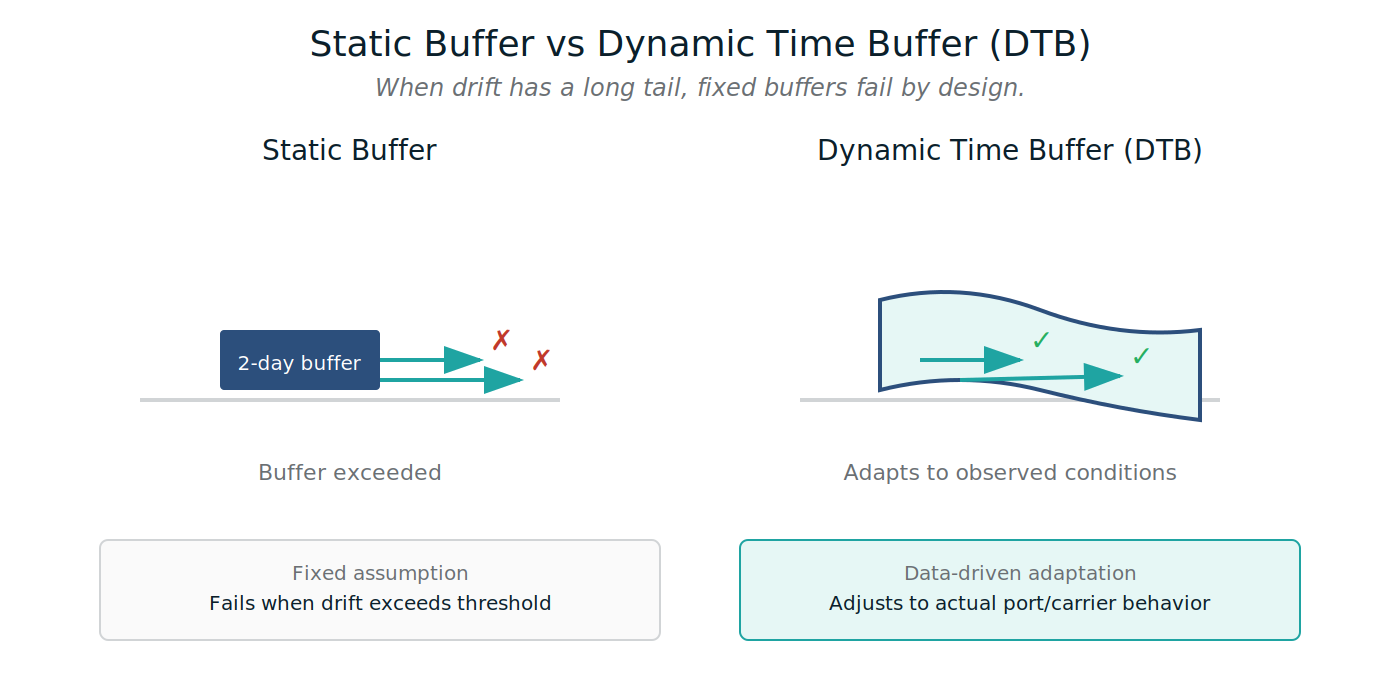

Section 8 - Why static buffers fail (and why this repeats)

Figure 8 - Static Buffer vs Dynamic Time Buffer (DTB)

Plain English meaning:

When drift has a long tail and late-stage changes are common, fixed buffers are routinely exceeded. Planning must adapt to observed behavior, not assumptions.

Before we move to the next carrier

A vessel can be “on time” and still break export execution if the receiving window shifts underneath it.

This Yang Ming edition shows:

- receiving window movement is the majority state in this sample,

- ERD drift becomes the dominant driver at higher thresholds (2+ and 3+ days), and

- volatility is highly port-dependent, with USSAV carrying the strongest signal.

Methodology and definitions:

Reliability Series - Methodology Appendix

https://www.tradelanes.co/blog/reliability-series-methodology-appendix

Next in the Carrier Reliability Series

Maersk - publishing soon.

Leave a Comment